How N. A. M. began

National Adoption Month began in 1976 in the state of Massachusetts as a way of bringing awareness to the plight of children in foster care. Designating a month to this consciousness-raising effort had its heart in the right place. Children need families.

This year’s theme

This year the focus is on sibling connections–which I hope means that siblings ought to remain together, rather than be separated by adoption. All of this is mostly good. Although, I’d prefer a campaign that got more to the heart of things. Something like “Adoption: Designed for Children Who Need Families.” Maybe even throw in a subtitle. Like, “Not designed for families who want children.”

N. A. M., a different perspective

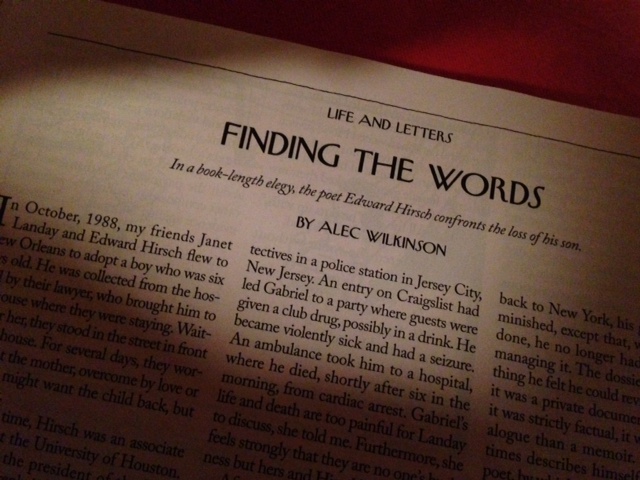

National Adoption Month can be a festival of pain and frustration for people who’ve been separated from their loved ones through adoption. Adoption is often touted as a fairy tale. But what if the tale doesn’t end happily ever after?

Explore adoption

Adoption is more complex than you think. Explore it from all points of view. There’s always plenty to read about adoption. Type adoption into the search box on Facebook and see what turns up. Then try it on Google. Check out the links under the “take action” tab in this blog. Maybe check out my book. Keep your eyes and ears open, and ask yourself how often it’s really necessary to remove an infant from a mother simply because she is very young, economically disadvantaged, or lacks family support. Is that ever really necessary?

Ask if adoption is necessary

I don’t think it was necessary in my case. If my narrow minded hometown/Catholic Church/Catholic school environment would not have made the lives of everyone in my family miserable, I could have kept my son.

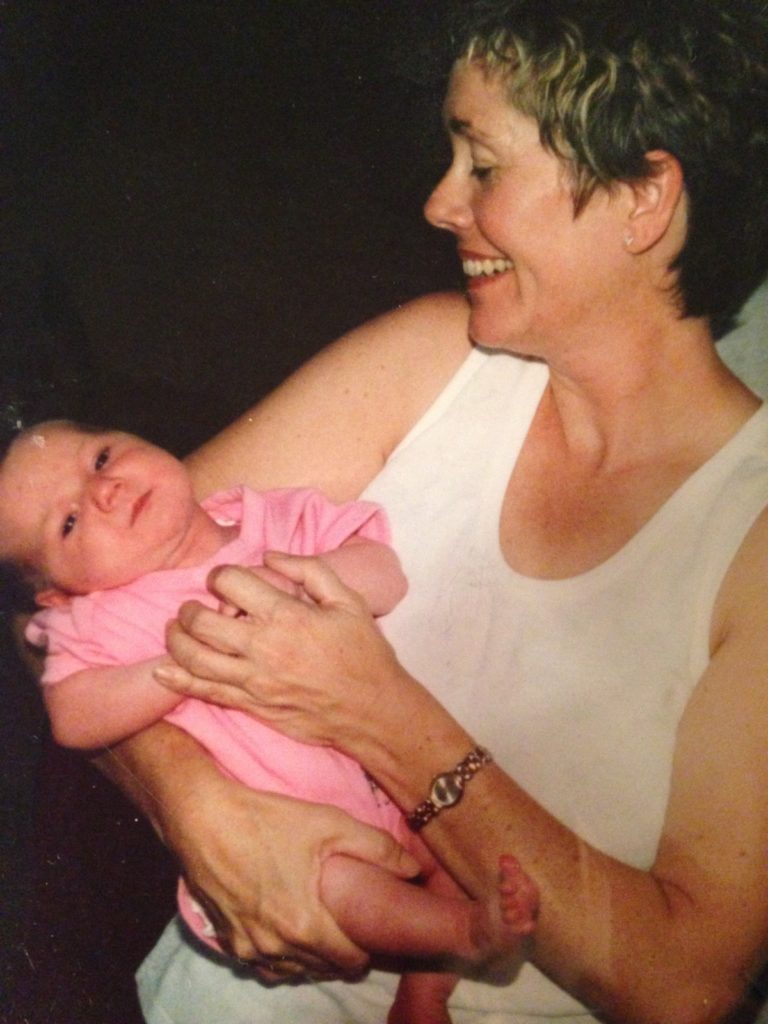

My sister was already married and living far from town out on a farm. What if I’d had a hideaway deep in a cornfield–a little cabin or house trailer? Every night I could have carried my baby down a stubbly path to her house. I might have had supper at the kitchen table with her and her husband and her two little kids. We might have sat together after the dishes were done, rocking our babies and feeding them their bedtime bottles. Then she’d carry her baby upstairs, and I’d carry mine back through the cornfield, fireflies lighting our way.

In our secret abode I would have loved my son, and he would have loved me. No one would learn my secret. Happy years would go on in this secret place, my clothes wearing thin while I witnessed my son learning to walk and talk. He would grown tall, and my braids would grow long, so long that they reached the ground.

That was the fairy tale I imagined as a 17-year-old. It’s not what really happened.